Are Haitians Hispanic?

Born to Haitian and Cuban Parents, Miami Herald Photographer

Carl Juste Talks About Teaching Caribbean Heritage

In the 1950s, Miami Herald Photographer Carl-Phiippe Juste’s father Viter Juste, a Haitian businessman, married Maria, the daughter of a merchant marine from Santiago de Cuba, in Port-au-Prince and started a family. Then, during a big wave of political turmoil, Juste’s father landed in jail for his support of a candidate in opposition to the government of then President Jean-Claude “Papa Doc” Duvalier. After his release, Viter and his wife moved to New York for a better life. In 1973, he settled his family in Miami’s Buena Vista neighborhood, which Juste would later coin “Little Haiti.”

Inspired by the Juste family’s story and their calls for community action, thousands of Haitians followed. At Viter’s bookstore Les Cousins Records and Books, new immigrants, many of them illiterate English learners, could get assistance with immigration papers and school enrollment forms. Viter and his wife strived to engage all kinds of political and social leaders, especially those representing the Hispanic and the Black community, rallying them around equal access to public schools for undocumented Haitian children, and pioneering Miami’s first adult education program.

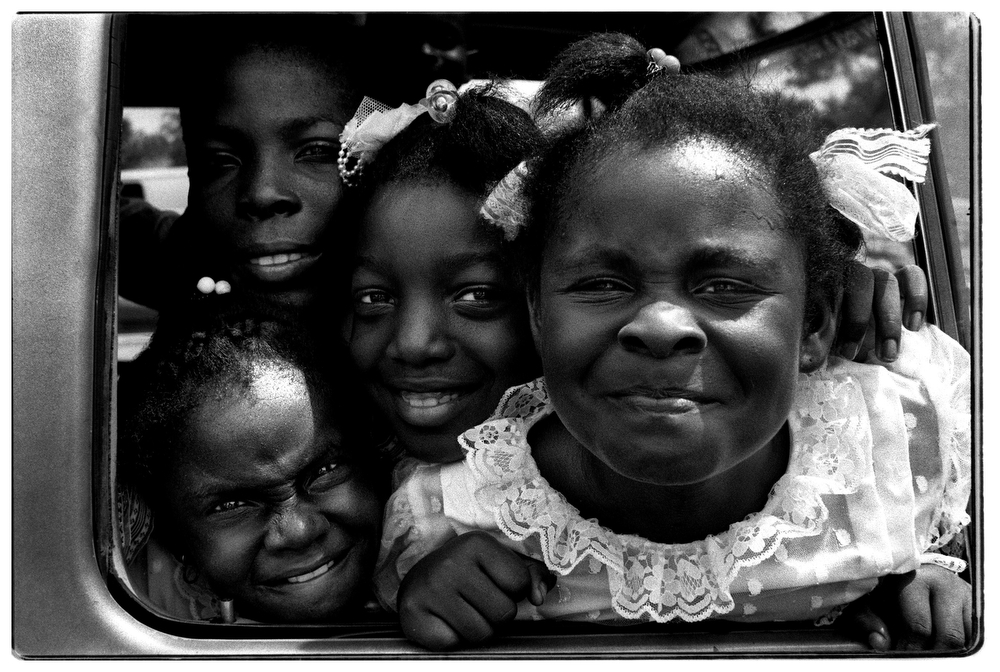

Carl Juste went on to obtain a bachelor’s in psychology with a minor in photo communications from University of Miami, and began a career as a photographer, first at the Miami News, and then, in 1989, he joined the staff of The Miami Herald, where he continues to work today. His assignments have taken him around the world with regular assignments in his native Haiti, as well as across the nation and throughout Florida documenting the day’s news and observing decades of identity politics. And much of that work has centered on what it means to be Haitian. In fact, he has won multiple photojournalism honors such as the Robert F. Kennedy Award, the National Headliners Award, and several Photographer of the Year International Awards, and he has exhibited his photos in galleries and institutions all across the Western Hemisphere.

Keep up with the latest from UnidosUS

Sign up for the weekly UnidosUS Action Network newsletter delivered every Thursday.

While UnidosUS focuses primarily on U.S. Latinos, it strives to promote civil rights for all peoples. In fact, in Florida, it works closely with representatives of the Haitian American community. Recognizing that Latinos and Haitians share many common cultural, linguistic, and political experiences, and that some people consider Haitians Hispanic, ProgressReport.co decided to close this year’s Hispanic Heritage Month with an exploration of that kinship. And since Juste has spent his life behind a camera lens, we thought he would be just the person to discuss it. We interviewed him at Iris Photo Collective Artspace, an organization he cofounded along with three other photographers of color to explore and document the relationship of people of color to the world.

Q: Do you consider Haiti part of Latin America?

A: I think there’s a lot of points of intersection, as well as parallel narratives, but I don’t think as a Haitian that would be the first box I would choose. Haiti is more Caribbean in terms of its history and identity, but a lot of Haitians do speak Spanish. In fact, many speak several languages. They speak indigenous Creole, which is an African and French mix, and they may speak French and Spanish, or even English fluently.

The whole island of Hispañola was fought over by the British, French, and Spanish, so I think those geographical and cultural intersections should be taught. I think it happens with an Afro-Latin intersect, and I consider French a Latin language, so I could be Latinx as much as anybody else, but I see it more as the intersection of common values and the connection to Africa.

And Haiti has had a role in the history of the region and the history of the United States. On January 1, 1804, Haiti freed itself in the middle of the height of plantation ownership and free workforce. It was the first time in world history that a slave rebellion had been successful. Talk about audacity of hope. They beat Napoleon and the French military, the most powerful military in the world at the time.

We Haitian kids grew up hearing about the role of Haitians fighting in the American Revolution, and how landowners who left Haiti after the Haitian Revolution went to New Orleans, Cuba, and places in between. All of that configures into the policies and into the various developments of the Western Hemisphere. I think for the most part, Latin America and the Western Hemisphere saw the revolution as a model for independence.

But that successful revolution has come with a price. Colonial powers found ways of disrupting the social, political, and economic benefits of this amazing feat by imposing military and economic pressure that weakened the autonomy of the country. That has continued to the current day.

Q: How did that contribute to greater blending of cultures across the region?

A: Haitians who fought in the revolution were probably one generation removed from being docked off the ship. Their grandfather or great grandfather probably came direct from Africa, whereas in my life, Haiti’s always been a place where ideas and races mix. There are places where you can’t tell the difference between Dominicans and Haitians. You have Haitians who speak Spanish as well as Dominicans, and you have Dominicans who speak really great Creole, probably better than me.

And Cuba, in terms of power and position, people of European descent were the ones who governed, but the population was far more mixed. The real indicators of origin are food, music, literature, and dance—the cadences—they’re not European. And there is, in fact, a large population of Haitian-descent Cubans I’m talking about—Haitian Afro-Cubans.

They left Haiti and went to Cuba right after the Haitian Revolution. There were many mixed-race ones who brought their servants with them, and then you also had Haitian merchants doing business back and forth, which my maternal grandmother’s father did.

But all that said, I would identify as Caribbean first, and I would think a lot of Cubans would voice their Caribbean side before their Latino side, at least the Cubans who are there now and who are woke. I know we throw that word around, but I mean Cubans who are aware of their melanin and who are aware of their African ancestry.

Q: Say you’re going to teach that intersectionality in a K-12 setting. Where would you start?

A: Well the first thing I always ask is who eats white rice? Who eats black bean, avocadoes, yams, and yucca? There might be different names for those staples, but white rice, arroz blanco, or diri blan—it’s just a change in name.

To certain ears, Haitian Kompa music sounds similar to salsa and merengue. They’re all drawn from the African expression. We also share Catholicism, Christianity, and the African religions.

There’s a lot more in common—basic stuff like guayabera shirts. Haitians wear those left and right. That’s what you wear when you go out and it’s hot. They serve a purpose, and I think what we share in common is always based on purpose.

Q: When your family came to Miami in 1973, Cubans were already the dominant immigrant group, and they were quickly integrating into South Florida. What was it like for your family to try and form alliances?

A: My dad spoke Spanish, so it was a natural fit, and he really looked up to the Cubans because he felt that would be a good prototype to follow. You get engaged first by business. You value education and hard work. These were all traits that had also been instilled in our community, but he really started getting engaged in the 1980s because he saw the racism, and he was very efficient at getting people to buy into this idea of equity.

Q: Let’s talk about the McDuffie Riots. Those took place on May 18, 1980, after four White Miami cops were acquitted of charges of beating Black motorcyclist Arthur McDuffie to death. How was that a turning point?

A: I remember exactly where I was during the McDuffie riots. We were at a party and we saw parents showing up saying “we gotta get out of here. The streets are on fire.” It was a confusing time. That was right in the middle of the arrival of Haitian boat people, who came fleeing the administration of Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, and Cubans who came with the Mariel Boatlift, when Cuban President Fidel Castro gave Cubans a temporary window for leaving the island. At that time, it was perceived that the African Americans didn’t have much love for Haitians, but towards the mid-1980s, they and the Cubans who came with Mariel began to understand that they were in the same struggle.

People from the Caribbean see race through a different lens. A lot of Haitians, Cubans, and Dominicans talk like there’s no blatant racism, that everybody’s getting beaten down because they’re poor, but if you look at who owns the land and makes decisions, it still tends to be people who are of White or lighter complexion and they hire dark-skinned people to do their hard or less desirable labor.

If my dad was alive today, he would be very upset with the system because he thought once Obama got elected it was going to be okay, that we were making that turn, but I remember telling him and my mom “there’s going to be a backlash.”

Q: You grew up in a multilingual household and studied in among a multilingual group of students, mostly Cubans. What kind of support do you wish English learners had then?

A: Developing a peer-to-peer curriculum. A lot of the things would have been better for me if my classmates and I had been put in a situation where we had to try and speak one language at any given time. For example, maybe lunch on one day would be all in Spanish. Peer-to-peer learning is more casual, more contextual, and less hierarchical. It happens in increments so you kind of rise together, and that helps the workforce, and you this all the time in Miami. A Cuban will say to a Haitian sa k pase?It means what’s up and it’s a quick way to kind of draw a bridge or establish rapport.

Bonjou is Buenas tardes. What is it about us humans that we wish someone a good morning or a good afternoon when your day’s been hell? There is a hope that your morning, your day would be good, that your evening would be good, that your night would be good. Well-wishing is something in common.

Q: What do you want all students to consider when we reflect on the crisis along the U.S.-Mexico border?

A: It’s Central Americans and Mexicans, but it’s also Haitians and Cubans. It’s the great migration. You had the Great Migration out of the Caribbean in the 1950s and 1960s, not only to America, but to Europe. These migrations are functional. They’re a product of a consequence. People move because somehow their social-economic ecosystem has been disrupted.

No one wants to leave their homeland, to pack and leave everything behind for a better job, especially if you’re coming to a place where you don’t speak the language, you don’t have the education or the support system. They do it out of extreme necessity. It’s a shot in the dark, and every great migration starts with that. That’s the parallel if it’s Haitians, Cubans, or Central Americans.

That’s why I started the Iris Photo Collective Artspace. It’s a safe space to talk about similarities and differences, to have an honest conversation. Some of the smartest and most interesting people I’ve ever met might not have a command of written or oral language, but they compensate by watching, by using all their senses.

Q: Today’s strategy for closing the achievement gap in under-served communities centers primarily on reading, math, and English. How do you think the arts, and more specifically photography, can bolster their confidence in tackling all the above subjects?

I think it’s about problem solving. Imagery is always in investigation because it’s not all written out for you. You have to figure it out. You have to think outside the box. You have to think about the role of symbolism. Think about the power that it gives them.

The Iris Photography Collective’s Visual Lab is available for curated youth photography workshops, and it will be offering a regular schedule of meetups for middle and high school students in the fall of 2020.