GUEST BLOG: How Adaptability Eased Me Through the First Phase of Teaching During COVID-19

Author Marcela Alvarez is a fellow with the UnidosUS National Institute of Latino School Leaders and a Teacher at Para Los Niños-Gratts Primary Center in Los Angeles.

Most teachers in America will probably tell you they went off to college, just as someone else in their family had done before them. They got their credentials and then settled in one grade or one school for a few years. My teaching career took a more winding path. I am the child of immigrants and I am the first in my family to obtain a higher degree. As a first-generation U.S. citizen, I was constantly reminded by my parents that I needed to find a stable career with good benefits. That is what my parents had worked so hard for their whole lives—to ensure my life would be better than what they lived in Mexico and what they lived here in the United States.

A year before graduating from University of California, Davis, I opted to apply to Teach for America rather than a traditional credential program. TFA was the fastest and most affordable pathway for me as a first-generation college graduate to get into the classroom. I bounced around more than most TFA instructors, teaching two different grades at two different schools in search of the best school site for myself. And because of budget cuts and personal life circumstances, I spent another two years at two other schools. In all, I have taught three different grade levels and three different dual-language models, within four traditional public and public charter schools in two different states.

That’s a lot of change, but now, in the midst of the myriad adjustments the educational system must go through to navigate the COVID-19 pandemic, I’m grateful. My unconventional early teaching experience and my upbringing have made me sensitive to diverse student populations and the unique challenges they face in these increasingly complex times.

For a year and half I have been a first-grade teacher at Para Los Niños-Gratts Primary Center in the heart of the Westlake neighborhood of Downtown Los Angeles. The majority of the 19 students in my class are English language learners, and most of them are low-income immigrants who fled poverty and violence in Central America. And while I speak Spanish, many of my students’ home languages are a Mayan dialect or some other indigenous language. Their sense of vulnerability and isolation outside of their own cultural group is exacerbated by the fact that they or their families are of vulnerable legal status. Because of these circumstances, many families find themselves crammed into small, single-family apartments with other families in their community. As a result, school isn’t just a place my students come to learn. It is a place where they could find consistency.

In early January 2020, just as the media first began reporting this new virus, I saw two students arrive at schools with masks. One has severe asthma and her mother notified the office that she would be sending her child to school with a mask as a precaution. As isolated language barriers and migration made them, some were already getting this news. In fact, many parents shared with me that their families in their home countries shared more with them about this new virus than our own news did. But as reports of the pandemic and its reach grew, I came to a point where I no longer felt comfortable doing my morning greeting with my students.

On March 13, LA Unified School District (LAUSD) announced it would close its schools for three weeks, returning the week prior to spring break. My organization, like other charter organizations throughout the county, followed suit. When the news broke, the entire staff at my school site rallied to create home schooling packets while doing their in-classroom teaching. We felt a huge sense of urgency to prevent loss of learning.

During the first week of the initial closure, my principal had us reach out to our students and their families to check in on their well-being, find out if they’d received their temporary home schooling packets, and ask about what access they had to technology at home. That way we could prepare for longer-term distance learning scenarios. The first phone calls were generally positive.

“Pues aquí estamos maestra,” the Spanish-speaking ones would tell me. “Here we are teacher, here at home, confused but all will be well soon.” Then they’d say I shouldn’t worry, that I should just take care of myself. But when I’d ask about their access to the technology necessary to keep their children learning at home, most said they only had a phone.

That worried me, and my concerns intensified just a few days later when Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and California Governor Gavin Newsom announced county- and state-wide “stay-at-home” orders.

With school closures extended, we teachers went into overdrive trying to figure out what a more robust distance learning program could and should look like.

Many of the parents were immediately furloughed, laid off, or told simply not to report to work, since they were not considered “essential workers,” and then, because of immigration status or lack of familiarity with bureaucratic systems, many of them couldn’t access unemployment benefits.

Factors like these made the second round of phone calls with families very different. Parents confided that without access to money or social services, they didn’t know how they’d feed their children or themselves.

Fortunately, LAUSD announced that it was setting up Grab-and-Go, a program in which families in need could drop by locations near their homes and pick up free meals. My organization, Para Los Niños, followed suit. But unlike LAUSD, Para Los Niños doesn’t have access to a large cafeteria staff across the district, so through the vendor, Student Nutrition Program, which provides meals for the students who attend Para Los Niños schools, with the support of school site and organization staff volunteers, Para Los Niños has been able to distribute meals at the Gratts Primary Center.

Parents were relieved to learn that Para Los Niños could distribute not just to families of students, but to all community members, and that they could take their children to those distribution sites and greet their teachers from a distance.

As the pandemic and the school closures dragged on, my weekly check-in phone calls revealed even more concerns. For example, parents said their children were beginning to exhibit anxiety, anger, and frustration over the closures and what that meant for their ability to follow through with their classroom work.

Not surprisingly, other teachers were noting similar patterns in their check-ins, and as such, we worked as an organization to troubleshoot. We quickly shared resources with families such as free internet services for qualifying low-income families. Para Los Niños then worked with partner other organizations to provide wraparound emergency services ranging from economic support to diapers. The Para Los Niños Mental Health department continued to accept and process referrals and to provide the psychological support children and families.

In order to support distance learning, school leaders within the organization decided that schools would distribute technology to students who demonstrated need. That was no easy task. How could we prioritize which students received what technology when we didn’t have enough to go around, and not all students even have home internet access?

Teaching via Zoom forced me to think on my feet more than ever. I constantly had to consider what basic resources my students had. Did they have pencils and scissors? What about the luxury of a quiet space to learn?

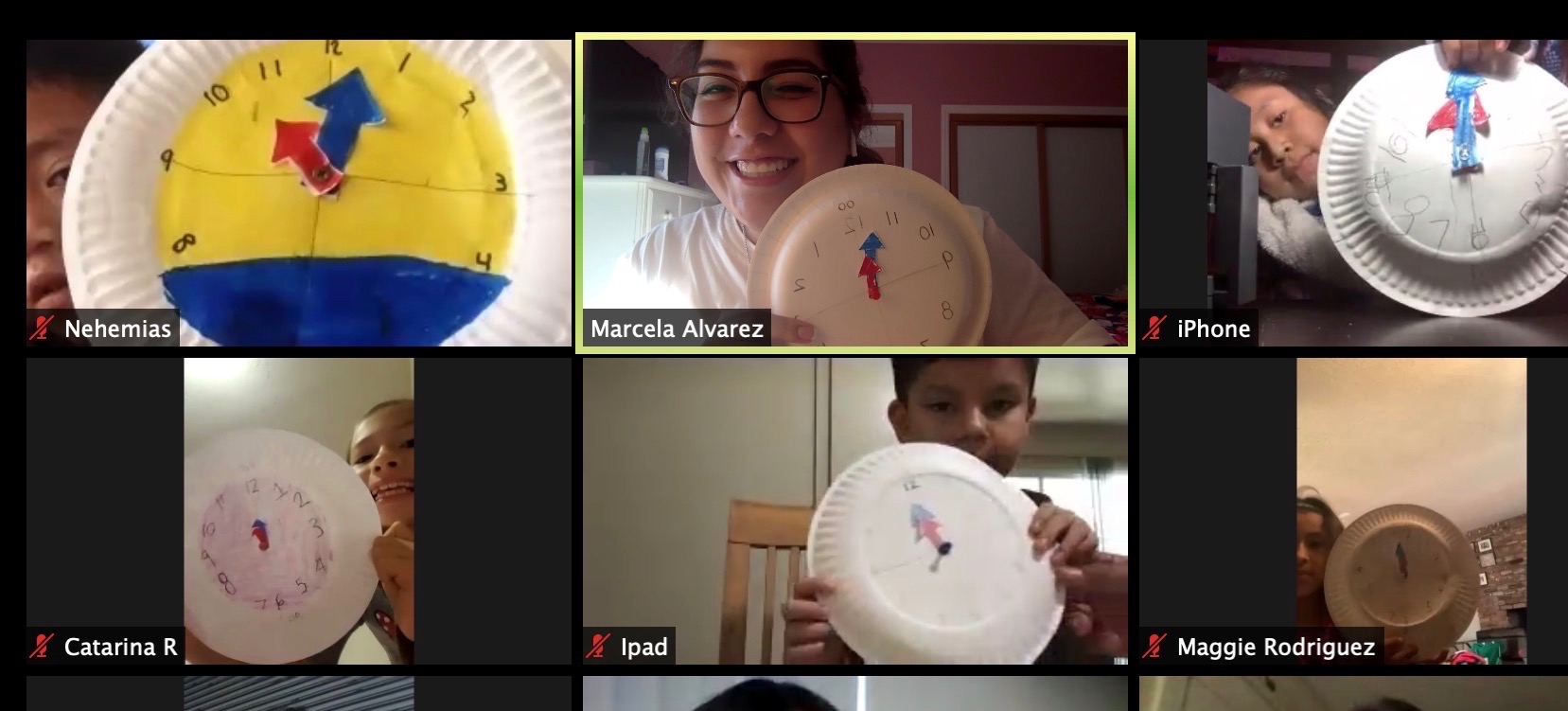

Through creative brainstorming and advance notice to families, my students and I were able to come up with some practical teaching opportunities. For example, we created clocks and practiced telling time by using a disposable plate, a piece of paper and a thumbtack. Two of my students didn’t have a thumbtack, so one used her mother’s earring, and the other found a screw. We also created high frequency word bingo boards. Through careful direction and repetition of the activity, students began to feel like they were back in the physical classroom.

But in spite of these achievements, I only consistently saw six of my 19 students on a twice a week basis. Their transition to online education still suffered from lack of adequate technology and internet access, as well as all the other logistics of trying to learn in a crowded house with stressed-out families. Sometimes families even struggled to get technicians to install or maintain their free internet service in a timely fashion, and sometimes the landlord and building managers even halted the service without explanations.

The schoolyear is now over, but the concerns are still very present. What happens after summer break? Under what circumstances will school reopen? What system will we be able to use and what are the associated costs and logistical challenges?

Up until 2020, no one in America enrolled in a teacher credential program expecting to create a virtual classroom during a pandemic. But here we are, and we must prepare for the worst-case scenario.

At a recent town hall event co-sponsored by UnidosUS and Telemundo, educators discussed many of these concerns. As they did, they reaffirmed what I had been thinking all spring—that we must purchase resources, not only crayons, paper, pencils, glue, and scissors, but pieces of technology and hotspots in order to support our students’ learning at home.

“I think that distance learning has had some bright spots. Many students have done well but overall, we know and we’ve seen data in our state that many of our students who are Latino English learners have struggled by not having access to teachers who can help with the homework assignments. Again, not having computers puts many of our students at a disadvantage,”California State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond said during that meeting.

As he noted, the California public school system was already working to address an achievement gap that disproportionately affects Latino and Black students, as well as students from low-income backgrounds before the pandemic. Now this public health catastrophe is threatening to turn that gap into a massive chasm, and we’ll have to keep that in mind as we scramble to create safe learning scenarios for fall semester.

“This is not a time for us to back away from equity; this is a time for us to accelerate learning,” Thurmond said.

As a teacher working within the school system he runs, that was music to my ears. Sure, I’m as tired as everyone else of hearing about the enormity of the challenge ahead, but looking back at all I was able to accomplish with my students and fellow teachers last spring, I’m confident we can keep fighting the good fight. It’s going to require us to continue pooling our diverse ideas and experiences to figure out what we have in our creative arsenals.

Having been through so many different schools and teaching scenarios, I know I can help get us up to speed by virtually attending my local school board meetings, signing up for public comment, contacting the California State Assembly members who represent my students’ communities in regard to maintaining and increasing funding for schools. And because I was once a student whose family experience was quite similar to those of the students I serve, I’ll find the energy to keep them at the center of my work, at the center of my mind and, most likely, at the center of my computer screen.